The Hitchhiker's Guide to `sys.path`

Disclaimer: This is a very technical blog. The ideas discussed here will not be immediately useful but if you are someone who is into developing python packages or production applications then this knowledge will surely help to become better at it.

Introduction

When you run a python script or python REPL, the python interpreter will just initialize a few variables and then will start executing your instructions. If you need additional functionalities, then you can import specific libraries using the import statement. The import statement does two operations; it searches for the named module, then it binds the results of that search to a name in the local scope. In this blog, we will discuss the first operation in detail.

The first and the most obvious question is, “Where does the import statement search for packages?”. Its quite simple, just run the following:

import sys

print(sys.path)

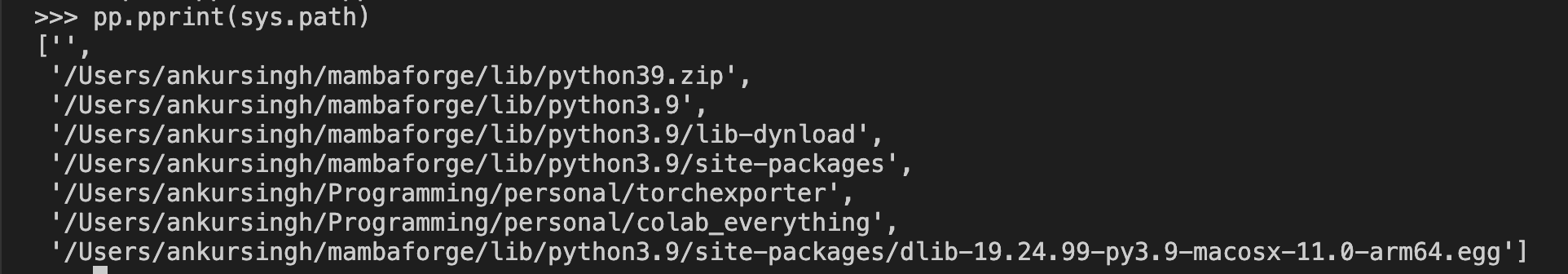

Here’s what the output looks for me:

As you can see, sys.path is just a python list with a bunch of strings (representing paths). import statement uses paths in sys.path list to search for modules/packages. You can easily import all the packages present in any of these paths.

Note: I will be using the terms modules and packages, throughout this blog. You can read this blog or watch this video to better understand the difference between python modules and packages.

One interesting thing to note is, Python has automatically adds Current Working Directory (CWD) to the list. This allows you load any python module/package that is present in the CWD, with the import statement.

Add absolute path to sys.path

Since, sys.path is just a python list, we can perform all the list operations on it. This will allow us to do many interesting things. Lets start with a simple use-case where your python module/package is present in some other directory (say /home/downloads). To load it, you can simply add the absolute path to sys.path list.

sys.path.append('/home/downloads/')

After executing the above line, you can load the module/package using the import statement. This is approach is not recommended, use it only for quick experimentation.

Importing from parent/upper directory

In python 3.4 and later, the support for relative imports was removed except when you are inside a package. So if you have multiple python modules that are organized in folders and sub-folders then you are going to have a hard time importing them (particularly when you will try to import modules from parent folders and above).

One possible solution is to add the absolute path of the root directory to sys.path, but this is not a good practice. You may ask why? because we are hard coding absolute path in our code. What if the location of the module/package that you are trying to import changes? Also, your code will not work in other systems. Unless and until they have the same module/package in the same location as yours. This requires you to make changes to your script before you can use it.

Ok ok Ankur, we get it. So, what is the solution? You already know it, relative paths. Instead of adding absolute path we will add relative path since, we know, our module/package will always be present in the same relative location. The important question here is “relative to what?”. This is where things get interesting, so pay close attention.

Relative to CWD

One approach is to import modules/packages relative to CWD (from where the python program is executed). For example, if your directory structure is a following:

mymodule

├── aa.py

└── b

├── bb.py

└── c

└── cc.py

Say, you are inside cc.py and you want to import some method/class from aa.py. To accomplish this, just add the following lines to the top in cc.py:

import sys

sys.path.append("../../") # added mymodule

import aa

--------- OR -----------

import sys

sys.path.append("../../../") # added mymodule's parent

from mymodule import aa

Now you can zip the mymodule directory and share it with anyone. Your code will work as expected in all other systems as well. But don’t start celebrating yet, there’s a catch. You can only run this code when you are inside c directory. You will get ModuleNotFoundError if you try to run the cc.py from any other directory. This happens because you are importing aa.py with respect to your CWD, changing the CWD will break the code.

An example of this approach is docker-compose. The command works only if you are inside a directory with docker-compose.yml file. Further more, the output depends on the directory you are running the command from.

You may ask, so what can we do if we want to run the cc.py from any directory? Don’t worry, we are going to discuss it next.

Relative to file

We know, aa.py will always be in the same location relative to cc.py. In the above approach we made our imports relative to CWD but the relative path to aa.py will keep changing from directory to directory. Hence, the above approach failed.

To make imports relative to cc.py file, we should append __file__ variable to our sys.path. __file__ is a special variable, in fact all double underscore attributes and methods are considered to be “special” by convention and serve a special purpose.

__file__ is used to get the exact path of any modules imported in your code. Simply put, inside any python script, __file__ variable stores the location of that file. So, inside cc.py file, __file__ variable will save the absolute location of the cc.py. You don’t have to define it because python will do it for you.

For the same directory structure as above, you can run the add the following lines at the top of your cc.py file.

import sys

from pathlib import Path

path = Path(__file__)

sys.path.append(str(path.parent.parent.parent)) # added mymodule

import aa

--------- OR -----------

import sys

from pathlib import Path

path = Path(__file__)

sys.path.append(str(path.parent.parent.parent.parent)) # added mymodule's parent

from mymodule import aa

Here I am using pathlib library, but you can os.path to get cc.py file’s parents. Now, you can share the code with anyone without the fear of it breaking. Also, you don’t have to worry about your CWD anymore. You can run cc.py from any where. Your code will keep work until the directory structure is maintained.

You may ask, why to go through all the hassle when you can simply cd into the directory and run cc.py? For small project, you don’t have to. But when you are developing production applications, you often have to use an IDE and, use features like debugging and testing. These features don’t work well if your code is cannot be executed from anywhere. Trust me, I have faced these challenges several times in the past and I have learnt it the hard way. Also, when you are working on a big project, the same code base will be shared and executed in numerous different systems. So, using absolute paths or relative paths w.r.t CWD is not advisable.

Turn your modules into python packages

Do you remember why we started this discussion? We wanted to import modules from parent directory. Apart from adding absolute or relative path to sys.path there is yet another approach. We can turn each of our directory into python packages.

Its actually very simple, create a new directory named root and move the mymodule directory to root. Then add __init__.py file inside each directory. This will signal to the python interrupter that this (i.e. root) directory is a package. This is how your directory structure should look after adding __init__.py file:

root

├── __init__.py

└── mymodule

├── __init__.py

├── aa.py

└── b

├── __init__.py

├── bb.py

└── c

├── __init__.py

└── cc.py

Now that you have turned your modules into a python package, you can use relative imports. Relative imports in python are a bit different from unix.

-

.-> current directory -

..-> parent directory -

...-> parent’s parent directory (in unix we use../../). This is a very subtle difference but can lead to import errors.

You can now make relative imports. This is how your cc.py should look now:

from ... import aa

No need to mess around with sys.path anymore. But now you cannot directly run cc.py as a script. You will have to run it with -m option as follows

python -m mymodule.b.c.cc

instead of

python mymodule/b/c/cc.py

This might look like a lot but don’t worry. Its pretty straight forward, just replace / with . and remove .py extension from the end.

Note: If you have never used -m option then I would highly recommend you to Google it.

Using setup.py

If you want to develop a python library and publish it on PyPI then you can use yet another option. Try reading the source code of any published python library, with very high probability, you will find a setup.py file in the root directory. setup.py file is the main file for building, distributing, and installing modules in python (using the Distutils). It’s purpose is to ensure that your package is installed correctly. Simply put, setup.py allows you to install any package using pip install -e . command.

Lets add a basic setup.py file to our root directory, and try to install it. The updated directory structure will look exactly the same with just a single new file:

root

├── __init__.py

├── setup.py # new file

└── mymodule

├── __init__.py

├── aa.py

└── b

├── __init__.py

├── bb.py

└── c

├── __init__.py

└── cc.py

Copy and paste the following content in your setup.py file.

# setup.py

from setuptools import setup, find_packages

setup(

name = "mymodule",

packages=find_packages()

)

Once last thing before we install the package: updating our cc.py file. The new file should look like :

from mymodule import aa

We are all set to install our package, cd into the root directory with setup.py and run pip install -e .. Great, now you can import mymodule from anywhere. Now, you know longer have to make relative imports.

Note: Setup.py is an advance topic in python. If you hear it for the first time, then here are few resources to get you started: official docs, practical guide to setup.py.

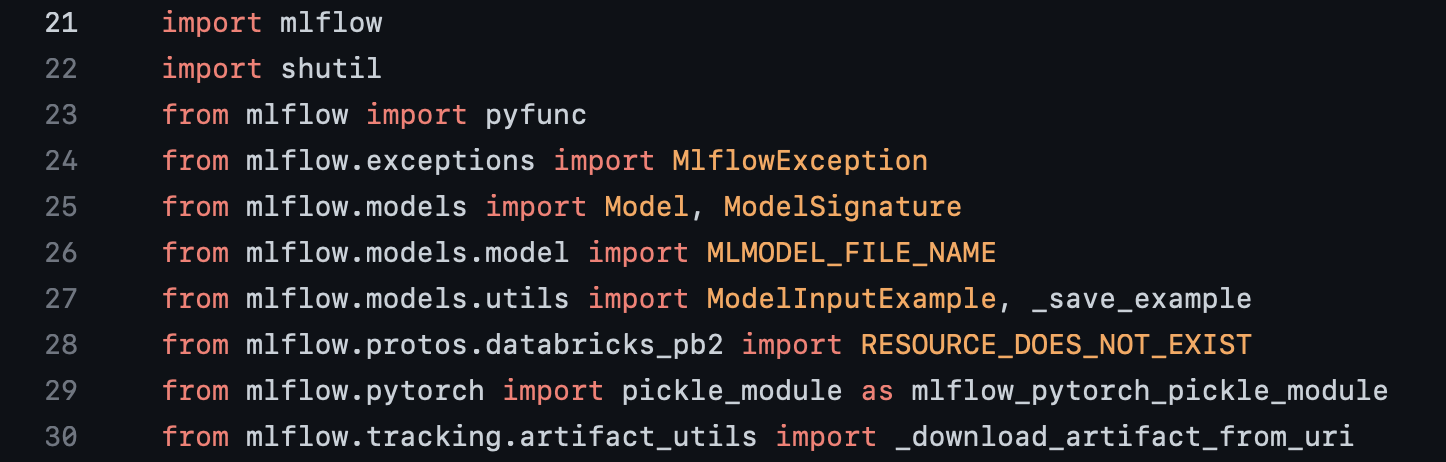

setup.py does nothing magical. It basically creates a symbolic link to your package inside site-packages directory. This is the most pythonic way of working with packages and for importing modules from parent directories. He is an example from mlflow github repo, the screenshot is from mlflow/mlflow/pytorch/init.py.

As you can see, even though this file is deep inside the sub-directories, you are able to import all the mlflow modules as if you are working on an external python file. This is made possible because of setup.py file in the root directory.

The same effect can be achieve by either of the following :

Adding absolute or relative path (w.r.t file) to sys.path inside each python file. Remember, this will make your code look messy and brittle.

Alternatively, you can add the custom module directory in PYTHONPATH environment variable, which will augment the default module search paths used by the Python interpreter. Add the following line to ~/.bashrc, which will have the effect of changing sys.path in Python permanently.

export PYTHONPATH=$PYTHONPATH:/custom/path/to/modules

The specified path will be added to sys.path after the current working directory, but before the default interpreter-supplied paths. If you want to learn how it works, checkout this Stack Overflow discussion

The 2nd approach looks good but often times when you are sharing your code with others or setting it up on some other system, you want to make sure that its self sufficient. After using developing in one system for a few months, its likely that you will forget about the extra export command you have added to ~/.bashrc. Having a setup.py file to do it for you, makes it super easy to share or migrate your code. Just unzip the code and run pip install -e ..

Summary

Here are all the important points to take away from this blog:

-

importstatement looks for modules and packages inside paths specified insys.path -

As

sys.pathis just a python list, you can easily add absolute or relative paths to it. -

In case of relative paths, prefer relative w.r.t file over relative w.r.t CWD

-

Changing

sys.pathis not pythonic and is kinda hacky. Your python linter will complain for sure. Also, you might have to change/updatesys.pathin multiple files. -

More pythonic approaches include,

-

Turning your modules into a python package

-

Adding

setup.pyfile and pip installing your package -

Add you module path to

PYTHONPATHenvironment variable (Not recommended, only do it if you can automate it & make it part of the package. For example, using bash script, makefile or something else).

-

That was all, signing off!

References

- Official Docs

- Python import: Advanced Techniques and Tips

- https://napuzba.com/attempted-relative-import-with-no-known-parent-package/

- importlib in python importlib in python has many cool features that allows one to dynamically import modules and packages during runtime.