Why you should always use Pathlib?

I have recently (4+ months) started using pathlib and I have never turned back to os.path. Pathlib makes it super easy to work with files and interact with the file system. But in these 4+ months, I have realized that “not many people use it”. I keep telling them its an amazing library, you must give it a try. Often, I tell them so much that they get confused 😅

This blog is another attempt to do the same. But instead of overwhelming the readers, I will try (my best) to be concise and to the point.

I will be using file path a lot, so let me formally define it for you.

File Path: name of directory and file in a file system.

Treating file paths as strings ❌

Python represented file paths using regular text strings. With support from the os.path standard library, this has been adequate although a bit cumbersome. For example,

import os

train = os.path.join(os.path.join(os.getcwd(), "data"), "train.csv")

This is how you create file path using the os.path module. Its a lot of code for just creating a simple file path.

Another problem with this approach is since file paths are not strings (but are treated as strings), important functionality is spread all around multiple standard libraries, including libraries like os, glob, and shutil. The following example needs three import statements just to move all text files to an archive directory:

import globimport osimport shutil

for file_name in glob.glob('*.txt'): new_path = os.path.join('archive', file_name) shutil.move(file_name, new_path)

Both these problems can be addressed if we treat file paths are path object (and not string). The pathlib module was introduced in Python 3.4 for the same. In fact, the official documentation of pathlib is titled pathlib — Object-oriented filesystem paths. It gathers the necessary functionality in one place and makes it available through methods and properties on an easy-to-use Path object.

Treating file paths as objects ✅

Using the pathlib module, the two examples above can be rewritten using elegant, readable, and Pythonic code like:

from pathlib import Path

## Example 1train = Path.cwd() / 'data/train.csv'

## Example 2path = Path().cwd()for file_name in path.glob('*.txt'): new_path = file_name.parent/ 'archive' / file_name file_name.replace(new_path)

Understanding pathlib

Creating Paths

There are a few different ways of creating a path. The most intuitional way is to use a string. Use the Path constructor to create a path object from the str:

# current working directoryPath('.')

# data directoryPath('data')

# train.csv inside data directoryPath('data/train.csv')

You can also use class methods like .cwd() (Current Working Directory) and .home() (your user’s home directory):

# current working directoryPath().cwd()

# user’s home directory)Path().home()

You can also create a new path by using / operator. I use pathlib library for this single operator. The / can join several paths or a mix of paths and strings as long as there is at least one Path object.

path = Path('data')

train = path/'train.csv' # file pathfiles = path/'positive' # directory pathsample = files/'book1'/'chapter1.txt'

Note: The /operator is used independently of the actual path separator used by the platform. More on this later.

Here are some more helper functions to check simple things :

path.is_dir()- returnsTrueif path is a directory; elseFalse.path.is_file()- returnsTrueif path is a file; elseFalse.path.exists()- check if the path exists or not method. ReturnsTrueif the path points to an existing file or directory; elseFalse.

Accessing Individual parts

Since we are treating our paths as objects, we can easily access different parts of a path as properties.

.name: the file name without any directory.parent: the directory containing the file, or the parent directory if path is a directory.stem: the file name without the suffix.suffix: the file extension

Let’s look at some code examples:

path = Path('data/train.csv')

path.name # train.csvpath.parent # datapath.stem # trainpath.suffix # .csv

Reading and Writing files

To read or write a file in Python we use the built-in open() function. With path object, you can use simply use .open() method to open a file

path = Path('sample.txt')f = path.open()

Note: Path.open() is calls the built-in open() behind the scenes.

For simple reading and writing of files, there are a couple of convenience methods in the pathlib library:

.read_text(): open the path in text mode and return the contents as a string..read_bytes(): open the path in binary/bytes mode and return the contents as a bytestring..write_text(): open the path and write string data to it..write_bytes(): open the path in binary/bytes mode and write data to it.

Each of these methods handles the opening and closing of the file, making them trivial to use, for instance:

path = Path.cwd() / 'sample.txt'path.read_text()

Final Words

You might have realized how easy it is to used pathlib. You can easily access different parts of the file path by using properties (like .name, .parent, etc). No need to write hacky string manipulation code. Many frequent operations like reading file-content are just a function call away. This is not a complete and exhaustive list of methods and properties offered by pathlib . You must check out the documentation for the complete list.

The primary point is not about having a lot of methods and properties. It about convenience and ease-of-use. pathlib makes working with files path, very intuitional. The code is concise and very readable. All this saves a lot of cognitive efforts for the developers/programmers.

Another advantage, pathlib makes your code more consistent across operating systems, by hiding all the peculiarities of the different systems.

Examples

Here are some examples of how to use pathlib for some simple tasks. I hope that it will give you a better idea.

Listing files in a directory

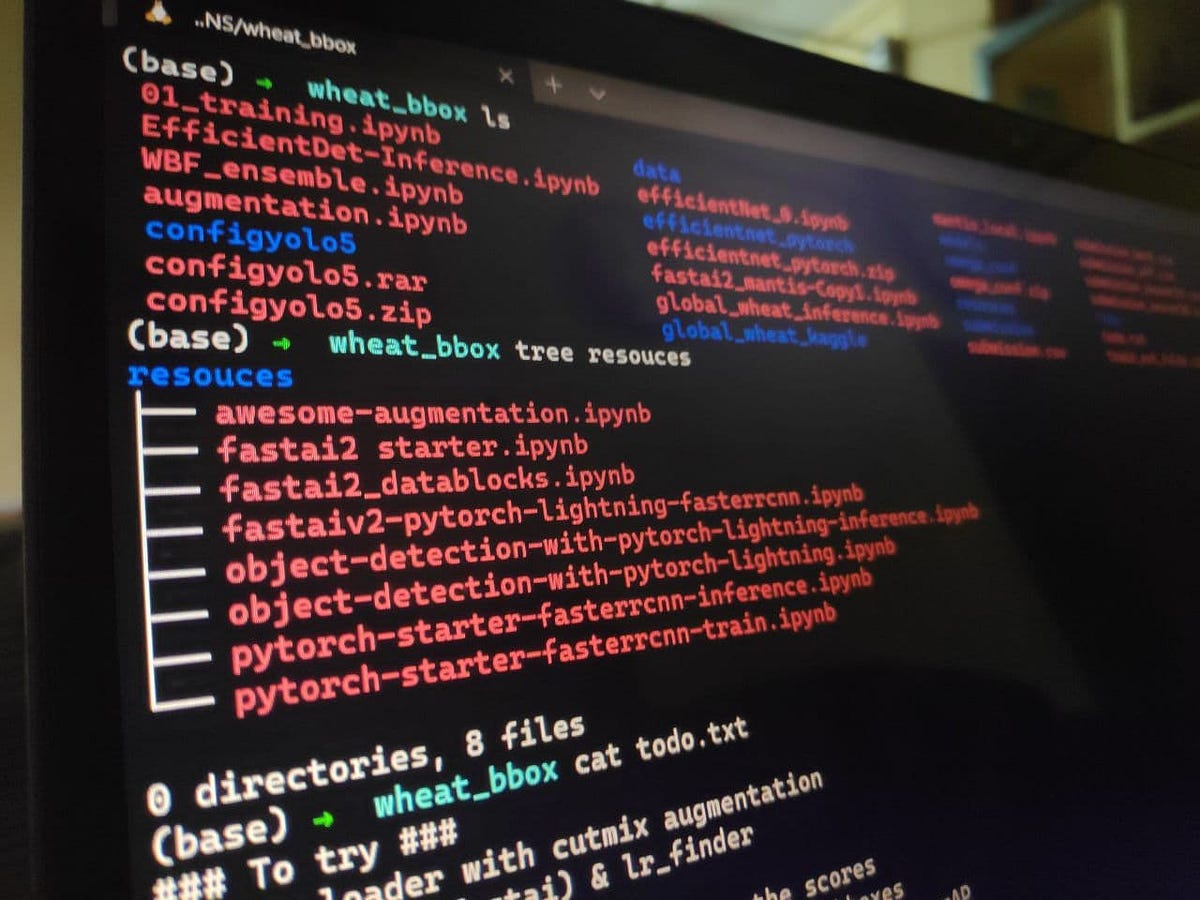

Lets replicate the functionality of ls command from bash shell.

def ls(path): return list(path.iterdir())

# list all filesls(Path().cwd())

Lets take it a step further and implement ls | grep command.

def ls_grep(path, pattern): return list(path.glob(pattern))

# list files with particular extensionls_grep(Path().cwd(), '*.csv')

# list files that match given patternls_grep(Path().cwd(), '*tmp*')

Note: You can use .rglob (recursive glob) instead of .glob to return all the files, recursively through all subdirectories.

Counting files

Lets count how many files there are of each filetype in the current directory.

from collections import Counterfrom pathlib import Path

exts = [p.suffix for p in Path.cwd().iterdir()]Counter(exts)

Display a directory tree

Let’s try to create our own version of tree command from bash shell. It prints a visual tree representing the file hierarchy, rooted at a given directory.

def tree(directory): print(f'+ {directory}') for path in sorted(directory.rglob('*')): depth = len(path.relative_to(directory).parts) spacer = ' ' * depth print(f'{spacer}+ {path.name}')

tree(Path().cwd())

Configuring kaggle-cli

You need to configure kaggle-cli before you can use it. The configuration process is a one-time thing. But because I use google-colab often, I have to configure kaggle-cli again and again. So, here is a small code snippet. Just change the path and you are good to go.

import osfrom pathlib import Path

path = Path('kaggle/kaggle.json')os.environ['KAGGLE_CONFIG_DIR'] = str(path.parent)path.chmod(600)

This is one of the easiest way of using chmod. I totally love it!

If you want one more such example, then do read this blog. The blog discusses “how to build a pandas DataFrame based on a directory structure”. It’s a great exercise to practice pathlib.

Reference

I have shamelessly copied everything from this blog. The intention was not to plagiarize but to present information in a concise manner. The original blog is pretty long because it discusses everything about pathlib and file systems. My intention with this blog was to share the things that I use pathlib for, and present practical ideas discussed in the blog. Something that I would ideally like to read, and share with others.

I would highly recommend every curious python programmer to read the original blog, its filled with great insights. I can’t thank them enough for the amazing blog. Link: https://realpython.com/python-pathlib/

Further Reading

Here is a list of some more blogs on pathlib.

- https://treyhunner.com/2018/12/why-you-should-be-using-pathlib/

- https://treyhunner.com/2019/01/no-really-pathlib-is-great/

I hope that more and more people start using pathlib. It’s too good to be ignored!